In this installment of Symbols & Symbolism we look at a reading from Albert G. Mackey’s Encyclopedia of Freemasonry on the meanings behind Clandestine, Clandestine Lodge and a Clandestine Freemason.

In this installment of Symbols & Symbolism we look at a reading from Albert G. Mackey’s Encyclopedia of Freemasonry on the meanings behind Clandestine, Clandestine Lodge and a Clandestine Freemason.

The video, deals with the first two subjects, the third is a subject of much contention creating clear vernacular delineation of what IS and what IS NOT considered by the various denominations of the fraternity.

You can find more installments of these educational pieces under Symbols & Symbolism, and on YouTube.

Clandestine

The ordinary meaning of this word is secret, hidden. The French word clandestin, from which it is derived, is defined by Boiste (Pierre-Claude-Victor Boiste – Dictionnaire universel de la langue française, first published in 1800) to be something:

fait en cachette et contre les lois.

Translated to mean – done in a hiding-place and against the laws (or, as translated by Google Translate – made secretly and against laws), which better suits the Masonic signification, which is illegal, not authorized. Irregular is often used for small departures from custom.

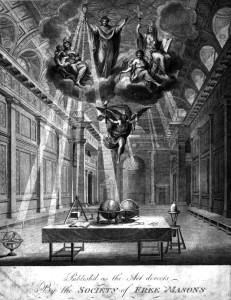

The Frontispiece to Noorthouck’s 1784 Constitution.

Clandestine Lodge

A body of Masons uniting in a Lodge without the consent of a Grand Lodge, or, although originally legally constituted, continuing to work after its charter has been revoked, is styled a “Clandestine Lodge.” Neither Anderson nor Entick employ the word. It was first used in the Book of Constitutions in a note by Noortbouck, on page 239 of his edition (Constitutions, 1784). Irregular Lodge would be the better term.

Clandestine Mason

One made in or affiliated with a clandestine Lodge. With clandestine Lodges or Masons, regular Masons are forbidden to associate or converse on Masonic subjects.

In the Book of Constitutions, Noortbouck’s comments read, first under the Abstract of the Laws Relating to the General Fund of Charity

IV, page ii:

No person made a mason in a private or clandestine manner, for small or unworthy considerations, can act as a grand officer or as an officer of a private lodge, or can he partake of the general charity.

Interestingly, they tell us their reasons:

And then Under the Making of a Mason (page 394 and 395), ART V

A brother concerned in making masons clandestinely, shall not be allowed to visit any lodge till he has made due submission, even though the brothers so made may be allowed.

and, ART VIII, page 395:

Seeing that some brothers have been made lately in a clandestine manner, that is, in no regular lodge, nor by any authority or dispensation from the grand master, and for small and unworthy considerations, to the dishonor of the craft; the grand lodge decreed, that no person so made, nor any of those concerned in making him, shall be a grand officer, nor an officer of a particular lodge; nor shall partake of the general charity, should they ever be reduced to apply for it.

From a Short Talk Bulletin, Vol.XIII, No, 12, from 1935 says definitively (for that time) that,

Today the Masonic world is entirely agreed on what constitutes a clandestine body, or a clandestine Mason; the one is a Lodge or Grand Lodge unrecognized by other Grand Lodges, working without right, authority or legitimate descent; the other is a man “made a Mason” on such a clandestine body.

It is, to no small degree, ironic that the definition of clandestine or irregular (i.e. a lodge or a mason’s status vis-a-vis a particular Grand Lodge) is also the factor that has largely allowed the concept to be so sorely abused and misapplied for decades,,,even centuries. Of course, there is no guarantee that the existence of a national governing body would have made much difference, for many years, in the schism between GL Masonry and the Prince Hall Craft. One might, however, at least expect that the logic of amity, rather than hostility, between the two would have been more apparent outside the context of local jurisdictions where there was (is) so much racial division.

In a sense, this is no less true today, with a renewed interest in the Craft among younger men and in the community in general. We face a potential (and, in some already apparent circumstances much more than potential) crisis over the need to protect the Masonic “brand” (if so crass a term is appropriate) against exploitation by those with no true affiliation with the Craft. What was, even in past periods of anti-Masonic hostility, a largely unnecessary defense (due to the public’s familiarity with the ‘genuine article’ of Freemasonry in their own communities) is now, quite possibly, a definite necessity, with the potential for so much misleading and often totally false ‘information’ being shared so rapidly and so widely.

It was, in the past, quite unlikely that one’s first impressions of the Craft would be formed by contact with ‘irregular masonry,’ but that likelihood had grown exponentially over the internet and is a matter of concern to us all. I would consider it very unlikely that an effective effort to neutralize the impact of this problem is to be found in the actions of individual GL’s acting independently.

In the eyes of the United Grand Lodge of England, who gave the lodges in the US their charter, Prince Hall became regular in 1784. If the Grand Lodges of the US claim amity with the UGLoE, then they should also claim amity with Prince Hall. However, we all know the history of that.

From Wikipedia:

“Unable to create a charter, they applied to the Grand Lodge of England. The grand master of the Mother Grand Lodge of England, H. R. H. The Duke of Cumberland, issued a charter for the African Lodge No. 1 later renamed African Lodge no. 459 September 29, 1784.”

The main group, who are considered irregular and clandestine, are the Grand Orients, and their subordinate lodges, which practice continental or liberal Freemasonry. They have broken about every charge and landmark that was created by the mother lodge. Not only do they allow atheists as members, but practice politics, as an organization, openly. They also still have round abouts with the church. Regular Freemasonry bans all of that.