by Jeremiah Torres, Quezon City, Metro Manila, Philippines

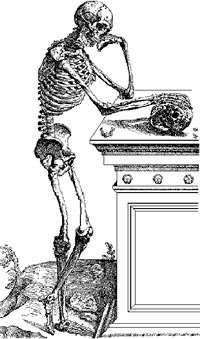

16th century woodcut

Every life, beginning with every birth, is a death foretold. Forgive me for talking about such a morbid subject; death is hardly a topic to be brought up in polite company. But this is what I’ve realized (having arrived at this realization in a rather circuitous way) while reflecting on my 26 years of existence. In contemplating the mystery of life, we must naturally consider its logical end, which is death, and which is equally a mystery. I recall the motto that I read somewhere adopted by the former Earls of Petersborough, “Avise la fin!”. Take care to consider the end. And so I begin this reflection with the end in mind.

memento mori

It took me 26 years, roughly a quarter of a century, to think of my own mortality. I know that people die. I know that death is a reality. I have stared at death in the eye, and watched many lives slip away from my hands inspite of aggresive resuscitation. In my first night duty at the medical wards, as a wet-behind-the-ears intern, no less than 6 people died on my hands, while I frantically pounded hard on their sternums, hoping for a miracle. And from that night on, I have witnessed death in many forms, and felt that precise moment when the last gasp of air, the last life-giving breath, leaves the vessel of the body, from a 4 month old infant at the NICU to a 90 year old woman at the ICU, and countless deaths at the ER and wards in between. In the hospital, and in reality, death is the great equalizer.

Everyone dies. No one is spared from death.

But to think that I, too, will die? Such a frightful thought, and one that I haven’t fully come to terms with. Until now.

You see, the medical curriculum, with all its good intentions, produces physicians who are taught to fight death at all costs. Thus, a physician-in-training will loathe and fear death, and will see death as an enemy throughout his/her practice. From the moment of conception, a physician attends to life in the womb, at birth, at all the life-stages…until death deals its mortal blow. All throughout his/her life, from the time s/he takes his oath, s/he will vow to preserve life. But death cannot be avoided. At one point, the physician must deal with death. The irony is that we, the doctors who are supposed to deal with death on a daily basis, do not find it easy to deal with our own mortality.

All men think all men mortal, but themselves. — Edward Young

You might wonder how I came to deal with my own mortality. Did I get sick? Was I diagnosed with terminal cancer? Have I rubbed elbows with Death? Encountered an accident? Had a near-death experience? No, it is none of the above. In the course of my own medical training, I have simply been fortunate enough to contemplate death — of my own and of others. It would have been easier to ignore it, as many of my colleagues did. It would have been easier not to think about it, as we were left without clear guidance from our mentors.

However, death is there. It cannot be denied. Every physician who confronts death will respond to it in a variety of ways: denial, anger, fear, loathing. I have simply embraced it. I have come to accept that I am not immortal, that a day will come when I will be reduced to ashes, and none of these would have mattered. I have come to realize that my own reactions, uncertainties, and fears before were neither unique nor unnatural. No one has any answers to this ultimate mystery, and no one can claim to be an expert. Those who go through the doorway can never return and tell us what the truth of death is, what lies beyond. Someone once wrote that “to be human is to accept and meaningfully endure the tension within us from the beginning – the tension between becoming and being, between being and perishing.” Is that so hard to comprehend?

Celebrating my birthday gave me another chance to reflect, as I do yearly, on my own life. It made me ask existential questions. It made me think of the mysteries of life. And when I got to asking how my life should be lived, thinking about death gave me the anwers. For the art of living well is simply …the art of dying well. The art of dying well: ars moriendi. To live fully, in order to die peacefully. Our living is, in other words, a preparing for death.

With death in mind, life becomes meaningful. The transitoriness of life makes us appreciate its beauty. We conduct life without the primping and the preening, without superficiality and pretensions. And we also appreciate its worth; we take care of our own life because we only get ONE shot at it. Someone once advised to “always try to learn from the mistakes of others, because we won’t live long enough to learn all of them by ourselves”. Life is too short to be making bad choices.

On the other hand, life should not be conducted like a business — it should flow like poetry. Many things bother us and keep us preoccupied. We fear getting hurt. We take calculated risks. We want to be “practical”. We are afraid to love and to commit. We hide behind masks of laughter, claiming to be content in our own secure little worlds. We accumulate. We value form over essence. We run our lives with our schedules, as if our whole lives depended on this “business of living”. We worry. Our lives are thus largely unfulfilled. Thinking about death teaches us to live otherwise, to live fully, to appreciate each day and seize all opportunities for growth and the tending of our souls. Carpe diem, so goes the well-worn cliche.

The prospect of death suddenly seems to be a very happy prospect! In Freemasonry, when a brother passes away, we never say that he “died”….we say that he was “called from Labor”, that he “dropped his Working Tools”. For me, and for people of my particular faith, this means Eternal Rest. It means a share in the divine life, to rest for all eternity. A dear brother in the Craft, Jose Rizal, echoed this very Freemasonic principle in the last three words of his “Mi Ultimo Adios”: Death is but Rest!

Seen from the vantage point of eternity, my life is just a parenthesis, punctuated by my own life-experiences. With all things that have a beginning, it surely must have an end.

But then, real Life would have only just begun.

And so, when I die, I do not want people to mourn. There will be no weeping. Instead, there will be dancing, drinking, holding hands, group hugs, fellowships, and endless parties, from dusk ’til endless dawn.

Avise la fin!

*Memento Mori: Remember that you too will die.

*Morir es descansar: Death is but rest.

Morir es descansar.* —Jose Rizal, “Mi Ultimo Adios” (My Last Farewell)

16th century woodcut carving: From Trechsel’s ‘Historic Images of Death’: Death and the Physician Artist: LÜTZELBERGER, HANS (1505-1526)

Pingback: Death in Freemasonry | Symbols and Symbolism | Freemason Information