Freemasonry, one of the oldest fraternal organizations in the world, has long been a symbol of Enlightenment ideals such as fraternity, liberty, and reason. Its values often clashed with authoritarian regimes, which saw its secretive nature and progressive philosophies as a threat to state control. Nowhere was this more apparent than in Nazi Germany, where Freemasonry under Nazi Fascism, along with other organizations advocating intellectual freedom and humanist values, became a target of severe repression. This section will explore the early relationship between Freemasonry and Nazism, highlighting the ideological tensions and setting the stage for the persecution that followed.

Freemasonry: Values, Secrecy, and the Seeds of Persecution

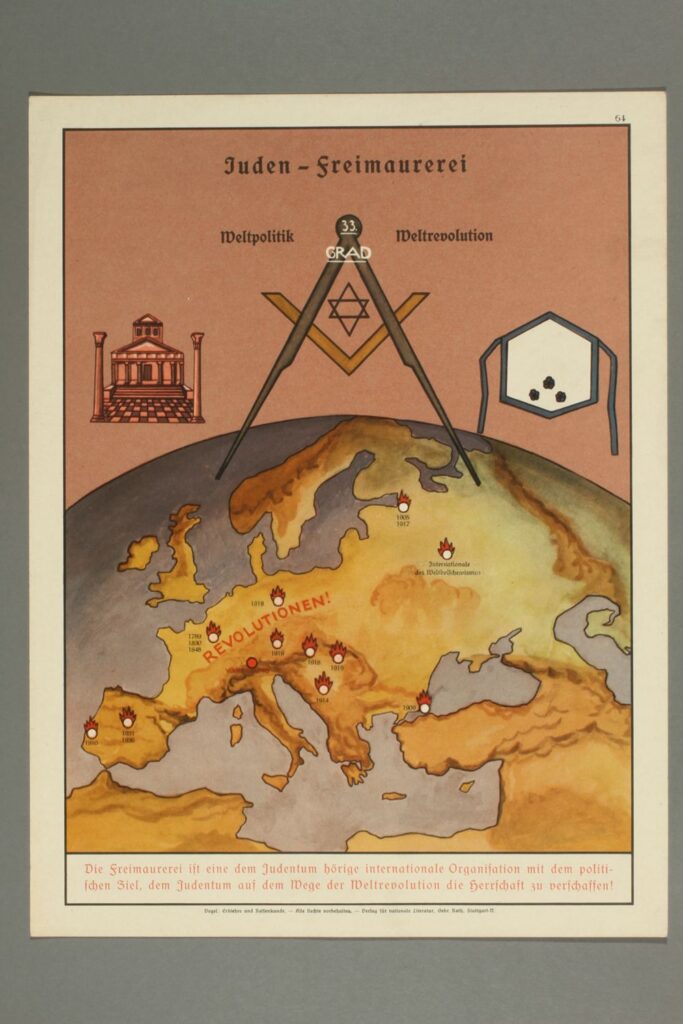

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives

Object | Accession Number: 1990.120.7

Anti-Jewish Propaganda Poster

Poster on cardstock with the title phrase: Juden – Freimaurerei

Source: https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn2583

Freemasonry, originating in the 17th century, has always maintained a degree of secrecy, operating with ritualistic ceremonies and selective membership that often invited suspicion. The organization’s values, which include a commitment to the Enlightenment principles of equality, intellectual inquiry, and religious tolerance, positioned it as a proponent of liberal democratic ideals. These values, however, became a point of contention in early 20th-century Europe, where authoritarian and fascist movements, including Nazism, sought to consolidate power by eliminating perceived ideological enemies.

Several factors fueled the Nazi Party’s hatred toward Freemasonry. Firstly, the secrecy and influence of Freemasonry were viewed as a threat to Nazi totalitarianism. Secondly, Nazi anti-Semitism played a crucial role in framing Freemasonry as part of a broader “Jewish conspiracy.” Freemasons, particularly in Germany, were linked in Nazi propaganda with Jews and international bankers, perpetuating anti-Semitic tropes of world domination

These associations made Freemasonry a primary target of Nazi ideologues who were building a narrative around racial purity, anti-Semitism, and the need to eradicate what they termed “foreign influences” from German society.

The Nazi View of Freemasonry: Ideological and Political Opposition

The rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in 1933 marked the beginning of an era of state-sponsored oppression of Freemasons. Hitler’s regime openly rejected organizations that promoted universalist ideas, including Freemasonry, which the Nazis saw as fundamentally incompatible with their vision of a racially pure German state. This opposition was outlined clearly in Mein Kampf, where Hitler linked Freemasonry with “international Jewry” and Bolshevism, forming a triad of threats to the Nazi worldview.

Nazi propaganda played a crucial role in spreading these beliefs. Anti-Masonic exhibitions were held in major cities like Berlin and Nuremberg, where Freemasonry was depicted as part of a grand Jewish conspiracy against Aryan purity. These exhibitions were heavily attended, reinforcing public fear and loathing of Freemasonry and further justifying the regime’s policies of suppression.

In addition to exhibitions, the Nazis circulated pamphlets, posters, and even films that painted Freemasons as traitors to the German state, often alongside anti-Semitic imagery.

Read: Freemasonry’s Resistance to Nazi Fascism and the Post-War Legacy of Persecution

The Nazi Party officially banned Freemasonry in January 1934, forcing all Masonic lodges in Germany to close their doors. By this point, many Freemasons had been subjected to harassment, property confiscation, and arrests. As part of their broader campaign against political dissidents and groups considered “enemies of the state,” the Gestapo began targeting Freemasons, alongside Communists, Socialists, and Jews.

Freemasonry and Anti-Semitism: Conspiracy Theories and Propaganda

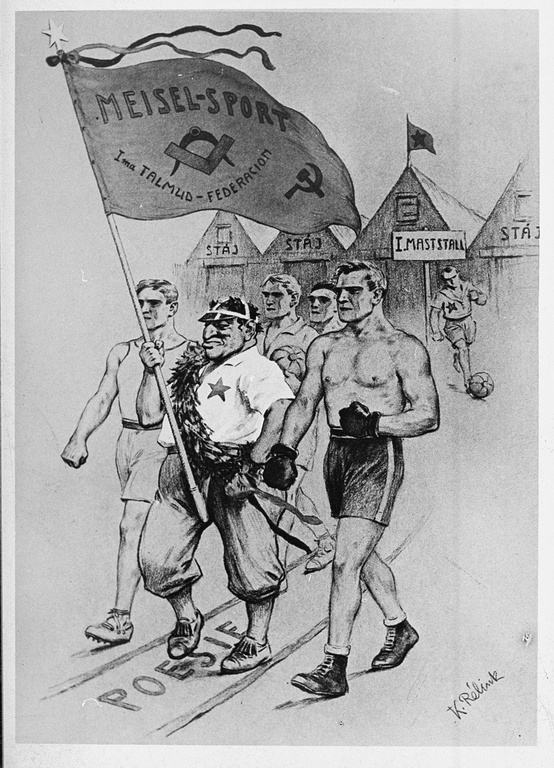

Copyright: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Provenance: Raphael Aronson

Source Record ID: Hauptarchiv der NSDAP stamp

Second Record ID: Collections: 2005.68

Source: https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/pa1036361

One of the most insidious aspects of the Nazi campaign against Freemasonry was its deep entanglement with anti-Semitism. Throughout the early 20th century, European fascist movements—of which Nazism was the most prominent—often linked Jews and Freemasons in conspiracy theories that blamed both groups for the perceived degeneration of traditional social orders. Nazi ideologues, most notably Joseph Goebbels, amplified these theories, portraying Freemasonry as a secret Jewish power structure that sought to undermine German sovereignty and unity.

The notion of a “Jewish-Masonic” conspiracy was not unique to Nazi Germany but had its roots in older anti-Semitic and anti-Masonic rhetoric that flourished in conservative and reactionary circles across Europe. However, the Nazis gave these ideas state legitimacy, using them to justify violent persecution. Freemasons, like Jews, were depicted as cosmopolitan elites who owed no loyalty to the nation-state, further driving public support for their repression.

Persecution Begins: The Ban on Freemasonry and Its Consequences

Following the ban on Freemasonry in 1934, the Nazi regime systematically dismantled Masonic institutions throughout Germany and occupied Europe. Masonic lodges were confiscated, their assets seized, and their members either forced into hiding or arrested. Freemasons were classified as “political prisoners,” and thousands were sent to concentration camps, where they were subjected to the same brutal treatment as other groups persecuted by the Nazis.

In concentration camps, Freemasons were often identified by a distinctive emblem: an inverted red triangle, which marked them as political prisoners. Many Freemasons did not survive the camps, while others managed to escape by disguising their affiliations or fleeing abroad before being captured.

Conclusion: The Legacy of Freemasonry Under Fascism

The suppression of Freemasonry under Nazi fascism represents a broader attack on liberal, democratic, and Enlightenment values. Freemasons, alongside Jews, intellectuals, and political dissidents, were targeted not only for their beliefs but for their perceived threat to the totalitarian state. The persecution of Freemasons serves as a historical reminder of how authoritarian regimes, particularly those driven by ideologies of racial purity and nationalism, view pluralism, tolerance, and secrecy as existential threats.

In the aftermath of the war, Masonic lodges slowly began to reestablish themselves, but the scars left by Nazi persecution remained. However, Freemasonry’s resilience serves as a testament to its enduring commitment to the principles of brotherhood, charity, and intellectual freedom—principles that fascism sought to extinguish.

From https://www.freemason.com/behind-masonic-symbols-forgetmenot/

“In 1934, members of one of Germany’s pre-war Grand Lodges, Grand Lodge of the Sun, began wearing the blue forget-me-not instead of the square and compasses on their lapels as a secret mark of identity. The “forget-me-not” is the informal name for the Myosotis flower, known for being small and having blue or purple petals. Throughout this whole era, these flowers appeared on lapels across cities and even concentration camps, worn by brothers whose love for the craft remained strong, even through the worst times. In 1947, when the Grand Lodge of the Sun was reopened, a pin in the shape of a forget-me-not was adopted as an emblem of that first convention by those who survived the Nazi era. It then was also adopted as an official Masonic emblem honoring those brothers who dared to wear the flower openly, and also recognizes the contributions of Masonic educators.”

Pingback: Freemasonry’s Resistance to Nazi Fascism and the Post-War Legacy of Persecution | Freemason Information

Pingback: Freemasonry In The Face Of Modern Fascism: Challenges, Resistance, And Survival | Freemason Information

Pingback: Christian Nationalism and the Future of Freemasonry: Navigating Uncertain Terrain | Freemason Information